History

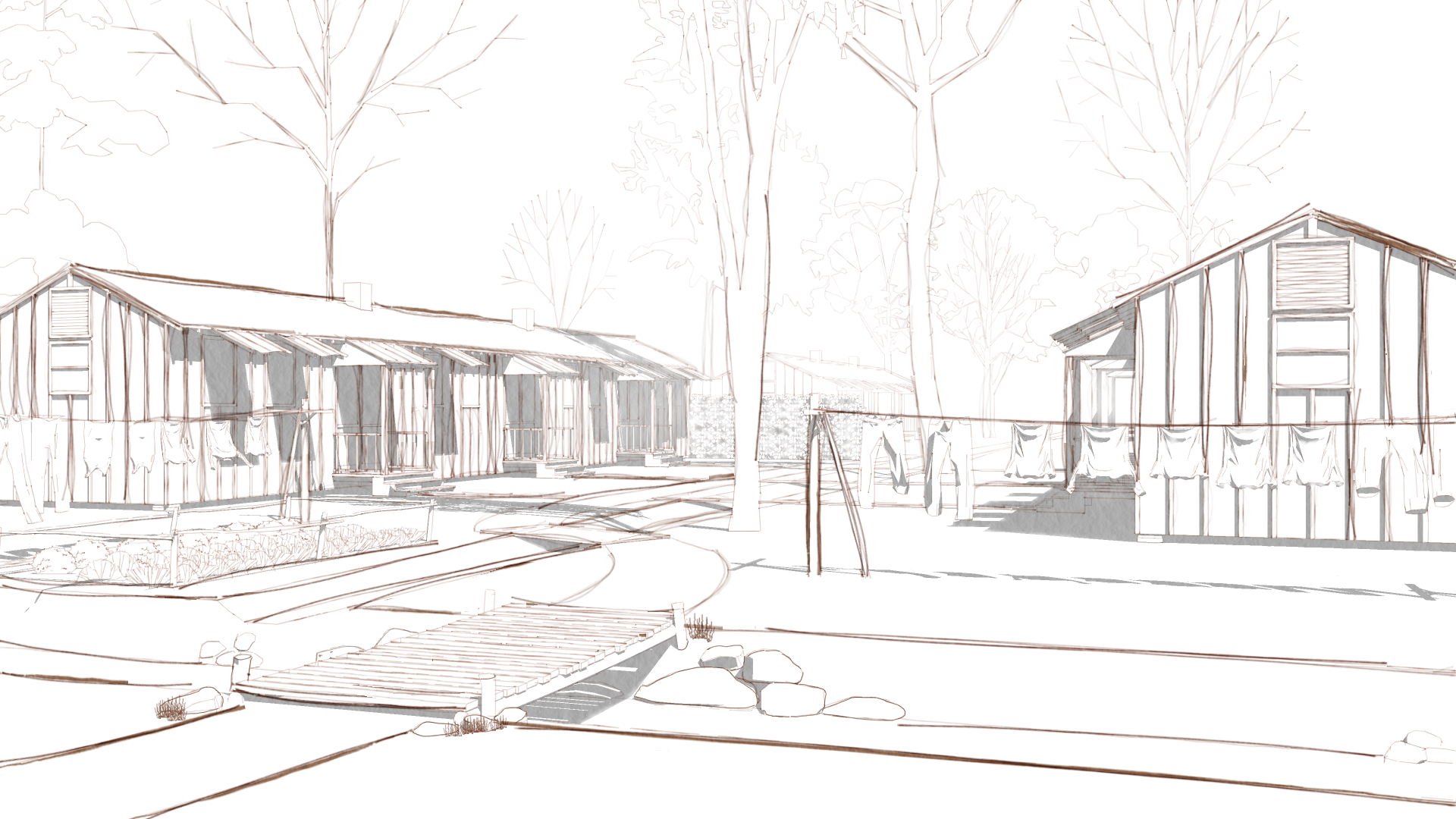

Architectural Illustration of a section of the Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center

(Glenn Gardiner, Center for Digital Initiatives)

Background

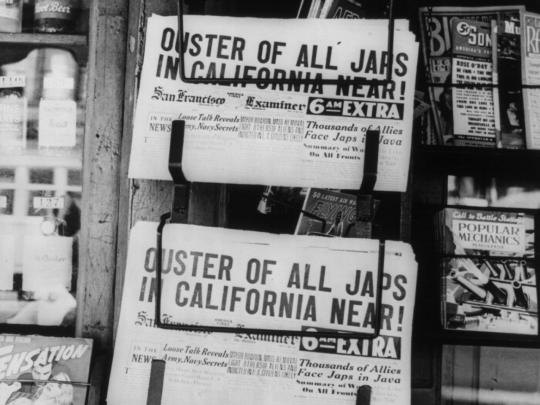

War hysteria, racial prejudice, and failure of political leadership led to the forced removal of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast following the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. One third of those removed were foreign-born Issei. Many Issei were more than 50 years old and prohibited from becoming American citizens. The remaining two-thirds were American born citizens–Nisei. Most Nisei were under 21 years old. These Americans left their entire lives behind, including possessions, homes, businesses, and communities and were imprisoned in 10 relocation camps across the United States, including Rohwer and Jerome (south of Rohwer) in Desha County, Arkansas.

Executive Orders

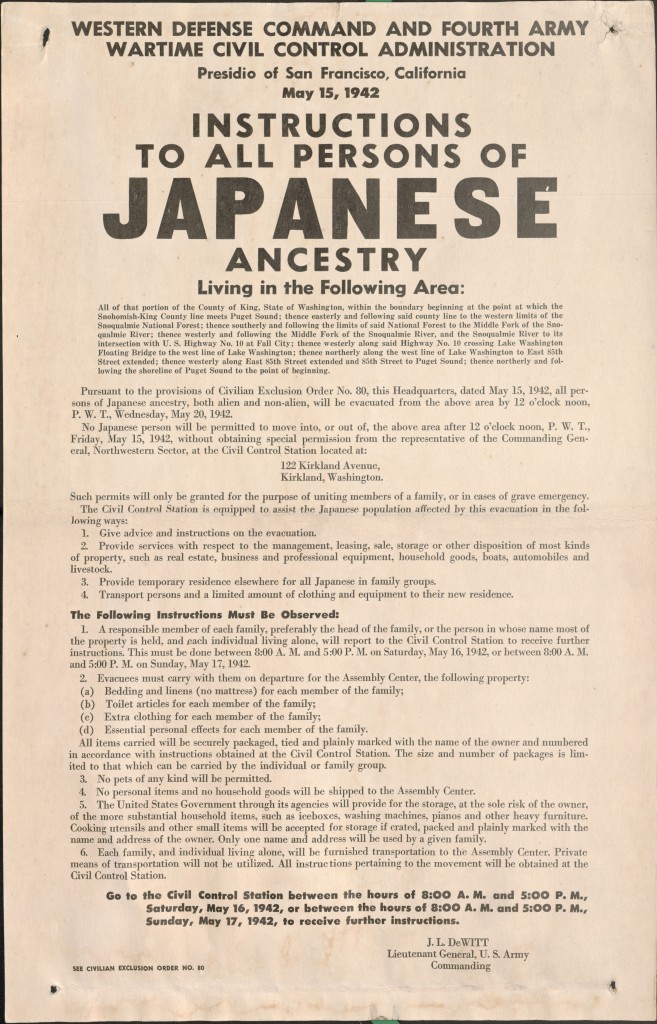

Because of Japan’s successful surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, many military and civilian authorities felt that the United State’s entire western coast was at risk of invasion. Communities and concentrated areas of people with Japanese ancestry were suddenly considered security risks even though no acts of sabotage or treason had taken place. Out of concern for national security and despite objections from several military advisors, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order #9066 on February 16, 1942, giving the U.S. Secretary of War the power to designate “military areas” and to enforce the exclusion of any or all persons within those areas. One month later on March 18, 1942, President Roosevelt followed this with Executive Order #9102, which created the War Relocation Authority and began the forced relocation of nearly 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry.

“We were all concentrated, densely concentrated, solely based on race,” George Takei, a former resident of the Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center said. “We happened to look like the people that bombed Pearl Harbor, and put in prison camps simply because of our race.”

Relocation Centers

Though they were officially known as relocation centers, these areas were more commonly referred to as concentration, internment, or incarceration camps. With watch towers, barbed wire, and armed guards, it isn’t difficult to see why these unofficial titles seem more fitting than “relocation center.”

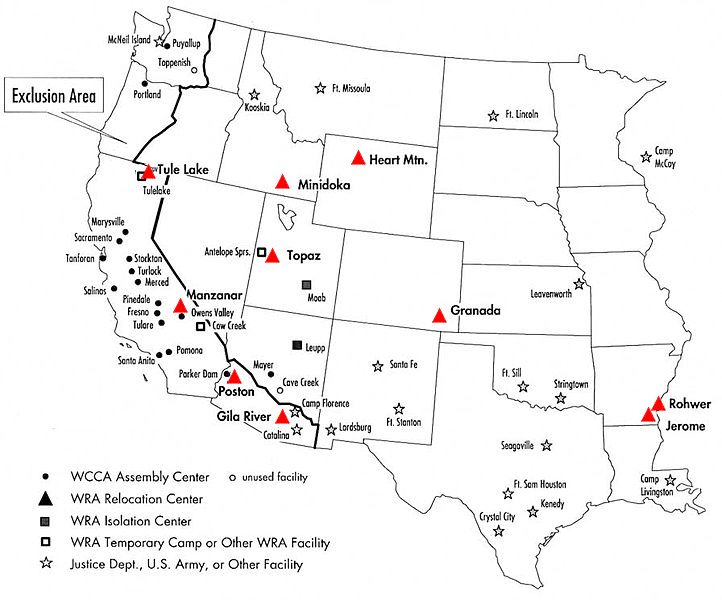

Areas for the new relocation centers were chosen by the War Relocation Authority because they were land-locked, remote, and had access to rail lines. There were ten relocation centers in total: Poston and Gila River in Arizona, Topaz in Utah, Granada in Colorado, Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Manzanar and Tule Lake in California, Minidoka  in Idaho, and Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas. So as not to delay the evacuation while the relocation centers were being built, persons of Japanese ancestry were forcibly removed from their homes in California, western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona to temporary holding facilities.

in Idaho, and Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas. So as not to delay the evacuation while the relocation centers were being built, persons of Japanese ancestry were forcibly removed from their homes in California, western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona to temporary holding facilities.

The Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center was located in swampy southeast Arkansas with 500 acres set aside for internee living quarters surrounded by 10,000 acres for farming and timber harvesting. The camp was separated into several distinct areas according to purpose: schools, open areas, the hospital, administration, and thirty-six internee barrack blocks. Each of these barrack blocks included twelve housing barracks furnished with only canvas cots and pot-bellied stoves, which were “home” for three to six families. These families were required to share a community lavatory and laundry building, a kitchen and dining hall building, and a recreation building. These living quarters were surrounded by eight watch towers, staffed with military police, and connected by barbed wire fences.

Internee Life

One of the most common struggles for Japanese internees was finding ways to earn money. Many internees continued to make payments on businesses and properties that had been left behind, and every family needed to buy basic necessities such as shoes and clothing. Internees who had previously worked jobs such as electricians, teachers, mechanics, and butchers were able to continue working in these positions within the camp, though their wages were significantly reduced. Others had to pick up new trades, including laboring in the fields to grow food for the barracks’ kitchens.

The harsh communal lifestyle had a negative impact on the traditional Japanese family structure, compromising parental authority and damaging the ties between family members.

Even though many were constantly struggling to make a living in this new reality they had been forced into, the internees left a positive mark on the local community. They showed the locals new methods of crop irrigation, impressed teachers with their hard-work in the classroom, and created distinctive art pieces that reflected their Japanese heritage.

Camp Closure

While the camp’s security had initially been quite intense, it gradually began to lessen until only one officer and 13 guards remained in 1944. This trend of decreased security continued and in January of 1945 the closure of all the relocation camps was announced. The internee evacuation began during the summer of 1945 and on November 30, the Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center was officially closed by the War Relocation Authority.

After the center was shut down, the barracks and other buildings were auctioned off and removed from the site. The land was converted to agricultural fields for cotton, soybeans, corn, and rice. Most internees immediately left the state, some returning to the West Coast to try and rebuild their former lives. Many more moved on to other parts of the United States. Only a few remained in Arkansas. A total of 168 Japanese American internees died during their incarceration  at Rohwer, most of whom were elderly. Those who preferred burial over cremation were laid to rest in the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery. Today, nothing more than the hospital’s decrepit smokestack and the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery remain of the original relocation center.

at Rohwer, most of whom were elderly. Those who preferred burial over cremation were laid to rest in the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery. Today, nothing more than the hospital’s decrepit smokestack and the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery remain of the original relocation center.

In 1945 two large concrete monuments were erected in the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery. The first was ornately decorated with floral patterns and artwork symbolic to both Japanese and American cultures. This monument was dedicated to all those who died while interred at the relocation center, including those who had been cremated rather than buried. The second monument commemorates the young men from the Rohwer Relocation Center who fought and lost their lives while serving in Europe in the U.S. Army’s 100th Battalion and 442nd Combat Team.